Zaltrap – a simple dosing error or not?

The recent approval of Sanofi/Regeneron’s VEGF targeted monoclonal antibody, ziv-aflibercept (Zaltrap) in combination with FOLFIRI, for the treatment colorectal cancer (CRC) after failure of prior therapy with the FOLFOX regimen has proven to generate quite a controversy.

The efficacy benefit, although modest at 1.4 months extra survival, is similar to that seen with bevacizumab (Avastin) in the same setting. The pricing, however, was clearly set at a premium at approximately $11,000 a month compared to less than half that for bevacizumab. I never thought I would be blogging about the price of Avastin actually looking very reasonable!

Unsurprisingly, a consensus that this would be hard to justify was met with a firm reaction from academic thought leaders, including a very strongly worded Op Ed in the NY Times from Drs Peter Bach, Leonard Saltz and Robert Wittes at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), who declared that the price differential was too steep and Zaltrap would not be included in the formulary there. Dr Saltz is well known for his opposition to high drug prices and the increasing cumulative cost of treating the disease.

Yesterday afternoon a new twist in the tale appeared with a new story in The Cancer Letter (paid subscription required) that Sanofi had halved the price of Zaltrap only two months after the launch in response to public pressure and criticism. There were several interesting things to note from the article:

- The drug’s price was pegged to the 10 mg/kg every two weeks dose of Avastin.

- If the company discounts the drug’s price without adjusting the Medicare reimbursement rate, this would create a windfall for prescribing physicians.

- Patients’ copayments would continue to be calculated based on the old price.

Based on this, I can’t see MSKCC changing their position, at least until the retail price changes, since there is no benefit to their patients in paying more than they would for Avastin.

Point 2 raised by the Cancer Letter makes me wince slightly. Although it doesn’t affect Academic physicians, since the Institutions purchase drugs from wholesalers or directly from manufacturers (in this case, Sanofi), in the community setting, oncologists purchase drugs from wholesalers, collect the patient co-pays and claim the reimbursement from the CMS or payers. In this case, they would make a bigger margin on prescribing Zaltrap over Avastin until the retail price is adjusted. This would be like going back to the old days of making huge margins on the spread with generics. Essentially, it offers the oncologists in private practice a large reimbursement incentive in the short term to prescribe Zaltrap over Avastin, at least until the price is changed at the CMS. The patient, however, is still forced to pay their copays at the original price and get no break from the Sanofi price reduction.

The dosing issue is slightly pertubing though. It’s well known that the dose of Avastin has usually been 5mg/Kg in colorectal cancer for some years, at least since 2004 from memory, while the dose in other solid tumour was indeed 10mg/Kg. Sometimes a loading dose of 10mg/Kg is used in patients with a high disease burden followed by the 5mg/Kg maintenance dose. The actual Avastin PI is very general since the drug was originally approved back in 2003:

“The recommended doses are 5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks when used in combination with intravenous 5-FU-based chemotherapy. Administer 5 mg/kg when used in combination with bolus-IFL. Administer 10 mg/kg when used in combination with FOLFOX4.”

Of course, what happens in practice is that drugs are sometimes approved with two different doses based on the trials at the time and clinical practice evolves with experience and knowledge. In this case, IFL and FOLFOX4 have given way to FOLFIRI and FOLFOX6 as the base regimens to which biologics are added. It didn’t take the CRC community long to realise that a 5mg/Kg dose worked just as efficaciously as the 10mg/Kg infusion when given with FOLFIRI and FOLFOX6, as well as being more cost effective.

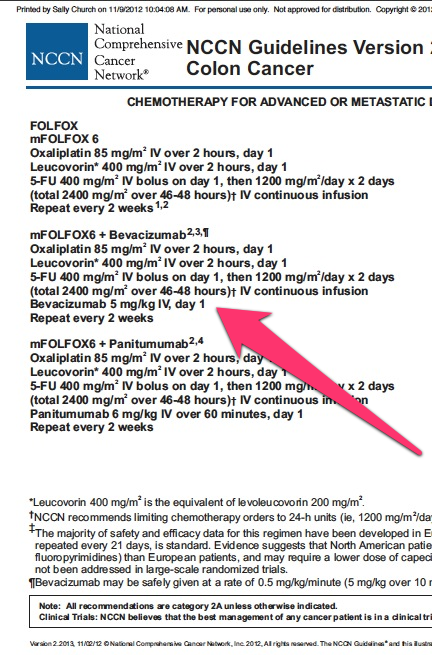

The community practice is reflected in the current NCCN Guidelines, which offer oncologists an overview of the standards for different regimens in different tumour types. You can see the recommended regimens and dosing schedules for colon cancer in the snapshot below:

Bevacizumab dosing in colorectal cancer

This confirms my suspicions and intuition having worked in the colorectal cancer field several times and not seeing much change there since 2004. Doctors are creatures of habit and safety, unless you give them a compelling (efficacy or reimbursement) reason otherwise. The NCCN Guidelines are created by a committee of Academic experts based on best practice and are usually followed by oncologists in private practice.

The moral of this story for pharma companies is don’t rely on product prescribing information (PI) for setting your pricing as they are often superceded by clinical practice as referenced in NCCN and ASCO Guidelines!