ASCO 2013 Highlights Part 2

It’s that time of the year when the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) hurtles around with alarming speed out of nowhere and everyone in Pharmaland goes, “ASCO, what already? Is it really June?!” Suddenly the month becomes the focus for many frantic hives of activity.

Immunotherapy

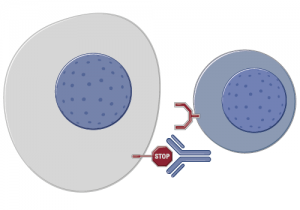

The last two years have seen some unprecedented changes in new therapies emerging to treat several different tumour types, both liquid and solid. One of the new trends that has begun to emerge is the new class of immunotherapy agents called checkpoint regulator inhibitors. These include:

- CTLA-4 (ipilimumab)

- PD-1 (nivolumab and lambrolizumab)

- PD-L1 (RG7446)

- OXO-40 inhibitors (more about those in another post).

This year at ASCO brings forth a lot of new data from the four compounds mentioned. In the video preview we have also attempted to explain how these antibodies work and why they are an important development beyond melanoma. There are data in several tumour types including melanoma, RCC and head & neck cancer at Chicago. In the recent thought leader interview with Dr Robert Motzer (MSKCC), he mentioned PD-1 as a hot topic to watch out for in renal cancer. However, I’m particularly looking forward to seeing the lung cancer data, which has the potential to be really stunning.

In this year’s ASCO video preview, we have included some graphics and an MOA video explaining how these immunotherapies are thought to work. Check it out below!

CLL

Another area that I’ve been watching for a while is chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which has languished a little in the shadow of it’s CML cousin. Not for long though!

There are a lot of exciting developments here beyond Pharmacyclics BTK inhibitor, ibrutinib. These include new CD-20 antibodies such as Roche’s GA-101 (obinutuzumab) and SYK inhibitors (whatever happened to fostamatinib, one of the hematology highlights of the 2010 ASCO?) where Gilead are now developing an early compound, potentially for combining with their PI3K-delta inhibitor, CAL-101, now known as idelalisib.

In addition, Infinity also have a PI3K-delta inhibitor, although they are further behind in development. We don’t know yet whether greater in vivo potency will translate to the clinic or whether also targeting gamma will add to the efficacy or introduce off-target kinase toxicities. Either way, it’s good to see so many targets and exciting new agents being explored for this disease.

Breast and Lung Cancers

On the solid tumour front, I was delighted to see new data in HER2+ breast cancer and ALK+ lung cancer. Interestingly, in both of these cancers, Pfizer and Novartis in particular are making inroads with a number of compounds including everolimus (Afinitor), palbociclib (PD-0332991) a selective inhibitor of cyclin dependent kinases (CDK) 4 and 6, LDK378 and PF-05280014, a trastuzumab biosimilar.

Pancreatic Cancer

My final topic that has some interesting developments is pancreatic cancer. Since the phase III Abraxane data from the MPACT study was presented at ASCO GI, Celgene have filed with the FDA and received Priority review, with a PDUFA date of September 21st. An update is expected at ASCO, along with tumour marker data and prognostic biomarker data. Threshold are presenting their phase III study design for TH-302 in the Trials in Progress section, but given the standard of care may well have changed by the time the data is mature, this may well be a day late and dollar short.

All in all, a good year can be expected for new data emerging at this year’s ASCO.

You can learn more about these topics, including insights on how PD-1 and PD-L1 immunotherapies work from the video highlights by clicking on the image below:

My ASCO preview video was freely available for several months but is now part of Biotech Strategy Blog Premium Content.