Transformative antibody technology in cancer research

Recently, I came across an exciting new development in a Nature publication and couldn’t resist teasing my Twitter followers with this terse statement:

Interviewed a scientist today re some really hot new technology that could be transformative in oncology. Will post early next week.

— Sally Church (@MaverickNY) July 18, 2013

Naturally, this mischievous tweet set off a lot of folks frantically trying to guess what I was referring to and the @replies came in thick and fast.

The National Science Foundation defines transformative as:

“Transformative research involves ideas, discoveries, or tools that radically change our understanding of an important existing scientific or engineering concept or educational practice or leads to the creation of a new paradigm or field of science, engineering, or education. Such research challenges current understanding or provides pathways to new frontiers.”

Many suggestions came hurtling in, most related to a drug or company, but actually what I was referring to was a transformative technology – the biggest clue was in the question 🙂

Bispecific antibodies, to be more precise.

I was completely inspired by an article by a group of scientists in Nature Biotechnology by Speiss et al., (2013) – the link is included in the references below and is well with reading. It’s one of those things you read and think, “Wow, wish I had thought of that!”

Genentech kindly gave me access to one of their scientists involved, Dr Justin Scheer (gRED), who explained the rationale behind their approach and what they hope to do with this technology. More on that in a moment, but first it’s a good idea to understand where I’m coming from.

Let’s take a look at both the potential and limitations of the various types being developed as cancer therapeutics, and the basics underpinning monoclonal and bispecific antibodies in more detail.

What are monoclonal antibodies?

Essentially, a monoclonal antibody is a manufactured molecule that’s engineered to attach to specific defects in cancer cells. They mimic antibodies the body naturally produces as part of the immune system’s response to invaders.

The immune system is trained to attack foreign invaders in the body, but it doesn’t always recognize cancer cells as enemies because they are formed from massive proliferation of the body’s own cells i.e. not foreign, unlike bacteria and viruses.

Monoclonal antibodies are usually directed to attach to certain parts of a cancer cell. An easy way to think of it is that the antibody ‘marks’ the cancer cell and makes it easier for the immune system to find and destroy.

How do monoclonal antibodies work?

The majority of currently available monoclonal antibodies are monospecific, i.e. having a single specific target e.g. CD20 or CD19, for example. The classic example in oncology is rituximab. Rituximab attaches to the CD20 protein found on B cells, which is associated with some types of lymphomas. When rituximab attaches to CD20, it makes the lymphoma cells more visible to the immune system, enabling them to be attacked and destroyed.

Treatment with rituximab lowers the number of B cells, including healthy B cells. The body will produce new healthy B cells to replace them and ensures that the cancerous B cells are less likely to recur.

While results with this approach have been impressive in some cases, there are limitations because cancer is highly complex and more than one target may be need to be addressed. This means that drug combinations are needed, increasing the complexity of clinical trial design especially in dose finding and MTD studies, risk of added or overlapping toxicities, increased costs etc.

Monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab have some other limiting factors though, as Speiss et al., (2013) observed:

“They lack natural Fc regions, they cannot bind to the neonatal FcRn receptor; binding to FcRn delays antibody clearance and improves pharmacokinetic (PK) properties.”

The lack of an Fc region also means that monoclonal antibodies typically cannot activate T-lymphocytes – because this type of cell does not possess Fc receptors – so the Fc region cannot bind to them.

A new potential solution exists

Antibodies that target two antigens are known as bispecific antibodies. Only one is currently available commercially (catumaxomab, Removab) and binds to CD3 and EpCam, although there are several in late stage development, including blinatumomab (Amgen) in ALL. The latter is interesting because it is part of the new generation of antibodies known as bi-specific T-cell engagers (BiTEs).

A bispecific monoclonal antibody (BsAb) is a manufactured protein that is composed of fragments of two different monoclonal antibodies and consequently binds to two different types of antigen.

Manufacturing a monoclonal antibody, while more complex than an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), is easier than a bispecific antibody. Much of the limitations seen so far with bispecific antibodies have been technological rather than clinical. What the Genentech scientists set out to do is succinctly described by Dr Scheer in the short Soundcloud below:

What are the advantages of bispecific antibodies?

The main advantage of bispecific antibodies is the ability to combine a cytotoxic cell (e.g. CD3) or ADC with a tumour specific protein target (e.g. CD19 or CD20) although a number of different combinations could be considered. In other words, you would get the ability to home in on the specific tumour target together with enhanced cell killing.

This could be a potent combination, except that technology-wise, they are difficult to engineer as Speiss and colleagues noted:

“… bispecific-antibody design and production remain challenging, owing to the need to incorporate two distinct heavy and light chain pairs while maintaining natural nonimmunogenic antibody architecture.”

There are some technological difficulties in engineering bispecific antibodies, though. Blinatumomab was mentioned as one example by Speiss et al., (2013) because:

“… some bispecific antibody fragments (e.g., the anti-CD19-CD3 single-chain fragment blinatumomab) are expressed as a single polypeptide chain they include potentially immunogenic linkers.”

What was fascinating about the Nature Biotech paper was that they reported on a new process they had developed to manufacture bispecific antibodies:

“We present a bispecific-antibody production strategy that relies on co-culture of two bacterial strains, each expressing a half-antibody. Using this approach, we produce 28 unique bispecific antibodies.”

One thing I thought was particularly cool about this novel approach is that bacteria are easier to manipulate and having a foreign component in the antibody will potentially mean that the human body’s immune system will hopefully pick it up more easily. Essentially, these new chemical structures could act as a powerful cancer homing device against specifically chosen targets.

The example used in the paper was a new bispecific antibody they engineered from co-cultures of EGFR and MET. Remember that Genentech/Roche already has a TKI against EGFR (erlotinib) on the market and a MET antibody (onartuzumab) in development. Neither of these drugs hit both targets and yet as Speiss and colleagues noted:

“MET and EGFR drive the growth of a marked proportion of non-small cell lung cancer tumors. MET and EGFR are often co-expressed and co-activated, and MET signaling can compensate for loss of EGFR signaling and vice versa.”

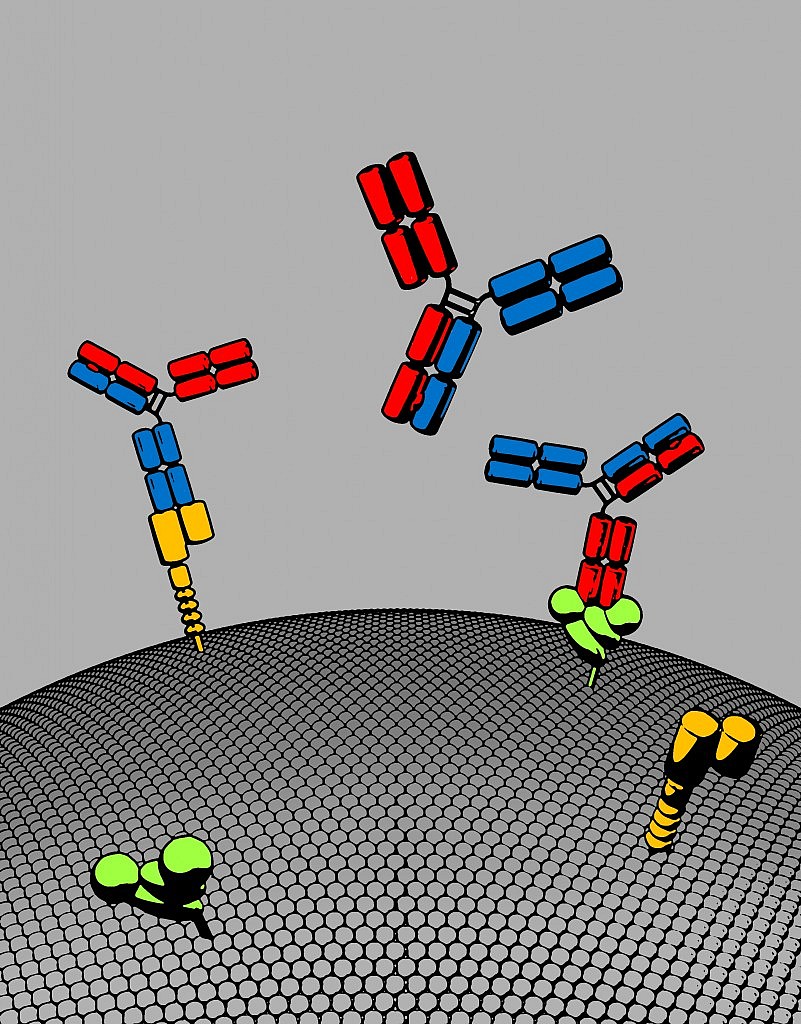

Image Courtesy of Roche’s gRED unit: Bispecific antibody with two distinct binding arms that inhibits both MET (orange) and EGFR (green). The bispecific antibody, shown here in red and blue, has a natural antibody architecture

As Dr Scheer observed, we don’t know yet is where the company will go with this exciting technology, but if the approach shows promising efficacy in future clinical trials, then it’s easy to see how multiple new bispecific antibodies could be easily developed for different tumour types, with far more potency and utility than single targeted therapies alone.

Stop and think about that possibility for a moment.

Transformative science isn’t always about finding a new target, sometimes the breakthrough is in removing the technological limitations to create a much more robust platform with enormous therapeutic potential. At that point, the biology, targets and imagination become the limitations, not the technology itself.

I have a feeling that this platform is a much more exciting breakthrough than many realise – it’s the sort of approach where you can see, to paraphrase a famous watch company’s ad – some day all antibodies will be made this way.

References:

![]() Spiess C, Merchant M, Huang A, Zheng Z, Yang NY, Peng J, Ellerman D, Shatz W, Reilly D, Yansura DG, & Scheer JM (2013). Bispecific antibodies with natural architecture produced by co-culture of bacteria expressing two distinct half-antibodies. Nature biotechnology PMID: 23831709

Spiess C, Merchant M, Huang A, Zheng Z, Yang NY, Peng J, Ellerman D, Shatz W, Reilly D, Yansura DG, & Scheer JM (2013). Bispecific antibodies with natural architecture produced by co-culture of bacteria expressing two distinct half-antibodies. Nature biotechnology PMID: 23831709