New advances in triple negative breast cancer

At ESMO last summer the initial phase II trial data on a PARP inhibitor, iniparib (sanofi-aventis), was presented in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). Unfortunately, I missed that session as it clashed with something else I wanted to see, but the data has now been published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The references are provided below for the link to the online article and accompanying editorial (subscription required).

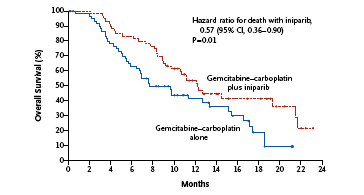

The front page of the journal provides a public link to the key overall survival data so far. As you can see, the bottom line is that the Kaplan-Meier curves do not cross over and a clear benefit in favour of the iniparib plus chemotherapy over chemotherapy alone is shown below:

The primary endpoint of the trial was progression-free survival (PFS). The median PFS in the iniparib arm was 5.9 months compared with 3.6 months in the chemotherapy arm. Overall survival (OS) was a secondary endpoint. This data (in the K-M curve above) showed that the OS in the iniparib arm was 12.3 months compared with 7.7 months among those who received chemotherapy alone. This translates to a 43% relative reduction in the risk of death.

Looking at the adverse event data closely, iniparib looks to be a reasonably well tolerated drug. The most common side effects in the iniparib group included neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, fatigue/asthenia, nausea and constipation. With regards to grade 3/4 adverse events, the most commonly reported ones in the iniparib group were neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia and fatigue/asthenia. There were two fatal adverse events (3.4%) in the chemotherapy-alone arm and three (5.3%) in the iniparib arm, all attributed to disease progression within 30 days of receiving study treatment.

According to the company (sanofi-aventis), the phase III trial in women with triple negative breast cancer is already ongoing and results are expected in 2011. Assuming these results are reproducible and no additional safety signals emerge, we can expect the data to be filed for approval with the EMA and FDA.

What does all this data mean?

To put this class in context, I first blogged about PARP inhibitors in 2006, before they became a hot topic and have followed their progress since (just type PARP in the search box to the right to see the other posts over time). Several others have since joined the clinical pipelines including olaparib (AstraZeneca) and veliparib (Abbott). What has been interesting from a strategy perspective, is that both olaparib and veliparib have focused largely on BRCA1 and 2 mutated cancers, whereas iniparib has been studied in triple negative breast cancer, which largely consists of basal-type rather than luminal histology. Of relevance here is that most BRCA1 breast cancers also have basal histology. Together, we could consider them both to have “BRCAness” as many breast cancer specialists have begun to refer them.

The latest article published last week was accompanied by a hard hitting editorial from Drs Carey and Sharpless (UNC). They noted several weaknesses in the current trial of iniparib, namely:

“The cohort was small, the end points were assessed by the investigators, the gemcitabine–carboplatin regimen is unconventional, and there were imbalances at baseline in prognostically important characteristics favoring the iniparib group.

We cannot tell whether the benefit from the PARP inhibitor accrued to all triple-negative tumors equally or whether the benefit preferentially accrued to a subgroup of BRCA-deficient tumors, with less effect in those without the deficiency.”

In other words, did a subset of women with TNBC and BRCA1 or 2 do better than those without? It’s impossible to tell from the data presented to date and would be a most instructive subset analysis.

Many of us will wonder about biomarkers too, and whether something will emerge from the trials that indicates a way to predict which women might best respond to the therapy rather than treat everyone with the disease to achieve a 56% clinical benefit. Could the other 44% be spared of the systemic effects of a therapy that is unlikely to work for them? Part of me is resigned to thinking this is a classic chemotherapy approach where you add in a new agent to standard chemo and hope that it moves the needle enough to prove significant. What we really need is a more detailed analysis with targeted therapies that looks at responders and non-responders to determine the underlying mechanisms for greater predictive or prognostic sensitivity.

The editorial also went on to state:

“In addition, unlike with iniparib, it has been challenging to combine several of these other agents with chemotherapy. Iniparib is a much less potent inhibitor of PARP1 (with approximately 0.1% the potency) than most other agents of this class.

The present study does not include a pharmacodynamic assessment of PARP activity in the patients receiving iniparib, and it is unclear whether the therapeutic efficacy of this agent correlates with PARP inhibition in these patients.

Therefore, the low potency, reduced toxicity when combined with chemotherapy, and possible BRCA-independent activity of iniparib distinguish it from other members of the class; at least part of its antitumor efficacy may be independent of PARP inhibition.”

In other words, it may actually be a PARP-like inhibitor rather than a pure PARP inhibitor. Clearly we have much to learn about PARP inhibitors and iniparib in particular, but hopefully some more useful granular data analysis will evolve from the phase III trial.

Obviously, we will have to wait for the confirmatory phase III results due next year, but if they are are positive and should iniparib receive approval, it may well be the first major advance for women with this type of breast cancer, who currently have a poorer prognosis than those with ER/PR+ disease. That’s good news for women with triple negative disease and something to be hopeful about.

References:

![]() O’Shaughnessy, J., Osborne, C., Pippen, J., Yoffe, M., Patt, D., Rocha, C., Koo, I., Sherman, B., & Bradley, C. (2011). Iniparib plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer New England Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011418

O’Shaughnessy, J., Osborne, C., Pippen, J., Yoffe, M., Patt, D., Rocha, C., Koo, I., Sherman, B., & Bradley, C. (2011). Iniparib plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer New England Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011418

Carey, L., & Sharpless, N. (2011). PARP and Cancer — If It’s Broke, Don’t Fix It New England Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe1012546

3 Responses to “New advances in triple negative breast cancer”

I’m so happy to read all this positive stuff about something so negative–pardon the pun…Keep up the good work in all ways. Please share your thoughts on the FB group: Triple Negative Breast Cancer

A new study shows that resveratrol

supplementation ‘“has the ability to prevent the first step that occurs when

estrogen starts the process that leads to cancer”’ (WebMD). I take the

Resvantage resveratrol supplement as it is the best quality one and the one

that most physicians recommend.

Access the links below for the scientific facts

about how resveratrol can help prevent breast cancer.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21729753

http://www.webmd.com/breast-cancer/news/20080707/resveratrol-may-prevent-breast-cancer

http://www.resvantage.com/

[…] New advances in triple negative breast cancer […]

Comments are closed.