Time to rethink cancer clinical trials strategy?

Recently, I’ve been pondering clinical trial design and wondering whether there is better way to do things, since much of the current concepts were based on cytotoxics that often had a very narrow therapeutic window. With the advent of oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), the model seems, well, a bit old and tired and doesn’t always help us develop the optimum outcome.

In phase I oncology clinical trials, for example, we seek to find the MTD, as explained by Drs Rubenstein and Simon (PDF download) at the NCI:

“The phase I trial is designed as a dose-escalation study to determine the maximum tolerable dosage (MTD), that is, the maximum dose associated with an acceptable level of dose-limiting toxicity (DLT – usually defined to be grade 3 or above toxicity, excepting grade 3 neutropenia unaccompanied by either fever or infection.”

What usually happens afterwards in cancer research is that the RP2D or Recommended Phase II Dose is suggested, often just a bit under the MTD.

The idea behind this is to maximise the efficacy, since after all, that’s what we’re aiming to achieve in the large scale phase III trials viz improved survival, whether it be progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS). PFS defines the time elapsed before symptoms worsen, while OS tells us whether people are living longer or not based on the therapeutic intervention.

But recently over the Thanksgiving Holiday I was reading Tim Ferriss’s “The 4 Hour Workbook” where he discussed the concept of ‘minimally effective dose’ or MED in the context of exercise and workouts. This lead me to wonder if this is something we should consider in oncology clinical trials – would the Pareto 80:20 principle work here too?

In other words, instead of seeking the MTD should we actually test for the MED and have less toxic side effects in the process? This potentially would also lead to better adherence and may even improve overall survival.

You probably think I’m nuts at this point, but hear me out.

Physicians and Pharma companies often forget that in the real world, patients fail to comply with oral cancer medications due to intolerable side effects that make their lives miserable. Not everyone is young, fit and healthy with an excellent performance status – multiple regimens and prior chemotherapy can really take it out of you, leaving you wiped out to face the next round. Even tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are not always a piece of cake to take. The constant niggly, but low volume side effects, can wear anyone down.

In support of this argument, let’s look at the impact of adherence on survival. I remember listening to David Marin from the Hammersmith present their findings on CML and compliance at EHA last summer. They observed that if adherence was less that 90%, then survival was dramatically impacted. You can see the difference in the curves on Biotech Strategy Blog. It still vividly sticks in my mind 18 months on!

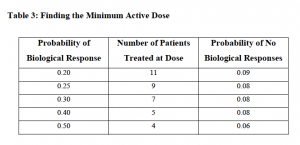

What’s also fascinating, is that in Rubinstein and Simon’s document, they also discuss the idea of “Finding the Minimum Active Dose” as shown in the table below, although I have never seen anyone discuss this in all the cancer conferences I have been to over the last 20 years!

Thus, if we were to reconsider the whole concept of higher dosing in favour of minimally effective dosing, then we might actually see better adherence and compliance on a broad scale and therefore, better outcomes for more people.

If we then add in the growing trend to combine two TKIs or a TKI and monoclonal, whether approved or as a novel-novel combination, a fresh approach to testing drug combinations rather than different MTDs starts to look more appealing.

Just a thought.

4 Responses to “Time to rethink cancer clinical trials strategy?”

I suppose that MED is sometimes roughly determined on a competitor’s established drug to improve trial results. (Tongue firmly in cheek.)

One typo: Four Hour Work*week*. Though there should be another tome on getting through spreadsheets more expediently…

You’re right, it’s the 4HWB not week, I was thinking of the exercises from something else methinks and got them confused.

Re: MED – LOL! So true of MEK inhibitors though.

You’d have to be able to recruit more patients to do parallel studies. After all, you wouldn’t want to have an MED that made the regimen 50% less effective than it could be at the MTD, for example.

As for adherence, that’s a logistical problem better solved by improved staffing and resources. Time and again, I find that people are simply scared and uninformed

When it comes to TKIs, achieving and maintaining maximum kinase inhibition in the malignant cell is the name of the game, right? So how about finding a personalized MED based on dose titration to cells isolated from biopsy in a companion IVD capable of measuring kinase activity inhibition? A TKI sensitivity companion diagnostic, if you will.

But then again, individual PK properties will probably confound the results.

Comments are closed.