Tumor Lysis Syndrome – what is it and why is it important in cancer research?

After the hullabaloo on Friday regarding AbbVie’s suspension of the ABT-199 trials following not one, but two, unexpected deaths from tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), a few people asked what is this condition and what causes it?

In simple terms, lysis is a medical word used to describe the break up or breakdown of cells – whether through decomposition, destruction, or dissolving. Thus, we have hemolysis, which is the destruction of red blood cells with the release of hemoglobin.

Tumor lysis, however, is a medical emergency whereby the sudden production of massive amounts of potassium, phosphate, and nucleic acids into the systemic circulation overwhelms the body’s garbage disposal units, the liver and kidneys. Urgent hospital treatment is usually required, often diuretics can be helpful to flush out and dilute the excess potassium (too much can slow or stop the heart beating), but sometimes kidney dialysis is also needed to speedily remove the excess production of the potassium. Death can unfortunately (but not always) result.

TLS is most common in aggressive, fast growing (high grade) lymphomas and acute leukemias (e.g. ALL), but is less common in indolent disease such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Given that AbbVie were testing their Bcl2 inhibitor in CLL, where TLS is rarer, some might think two deaths from TLS a surprise, especially given the positive results reported at the recent American Society of Hematology (ASH) meeting in December (more about the ABT-199 data).

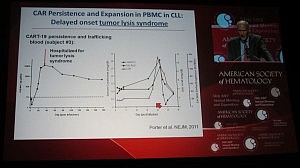

This is not the first time TLS has been reported in leukemias though. Carl June (U Penn) presented the data on their chimeric antigen receptor therapy (CART), a collaboration with Novartis, in CLL and also childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) at ASH. Their lead therapy, CTL019 (formerly CART19), also leads to TLS in both ALL, where it is more common, and CLL patients, although he did state in the Ernest Beutler lecture that the patients received urgent renal dialysis and recovered.

Interestingly, Dr June described the TLS as occurring not immediately, but delayed until 20-50 days post infusion. Given what we know about autologous cellular immunotherapy, a delayed response is not a surprise, but in line with our scientific knowledge to date, since it takes a while post apheresis to activate the T-cells.

You can see from Dr June’s slide that the serum levels of creatinine and uric acid spiked around day 20, but the patient was hospitalized for TLS a few days later:

It is possible that the TLS occurs in CLL as a result of rapid efficacy and on target effects – in other words, the treatment is doing it’s job of killing the cancer cells, perhaps a little too well.

Final thoughts…

We will have to wait and see what happens with the larger randomized phase 3 trials for both ABT-199 and CTL019:

- We don’t yet know whether the effect in ABT-199 is a dose-schedule issue or a compound structure issue (especially given the reformulation from the original navitoclax molecule).

- If TLS is a persistent toxicity issue and efficacy is durable, then it may well limit both potential treatments to Academic centers with experience and resources to quickly monitor and treat such sudden events in future.

- These are exciting molecules but care is clearly needed in managing the toxicities.

Contrast these approaches with ibrutinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets Bruton Kinase, where the effects appear to be slow but steady inhibition of a key target driving CLL proliferation. TKI therapies are very Community oncology friendly in comparison, particularly for indolent diseases. Although the Bcl2 and CART therapies look very promising, they may need a more careful and judicious approach to reduce the risk of sudden deaths from TLS.

6 Responses to “Tumor Lysis Syndrome – what is it and why is it important in cancer research?”

Hi Sally, I used to study apoptosis inhibition in CLL. Fascinating (and amazing, to an oncologist) that you can get a tumor lysis syndrome in CLL. Indeed, it suggests some of these drugs are hitting the right cellular pathways.

Hi Elaine, yes that’s a great way to describe it – I was fascinated, awed and yet wary listening to Carl June’s talk at ASH when he put up that slide (there was one for ALL too) explaining what happened. You realise “wow this is really working” and “oh my, they drop off a cliff” simultaneously.

Gave me goosebumps, frankly.

Is there no role for rasburicase?

You would think so, Terrence, but a quick search on various patient sites suggested that in a few CLL patients who reported a near fatal experience with TLS that Elitek didn’t seem to be effective at all. I sense from the research that the problem is that while TLS is pretty rare in CLL, when it happens, it’s a massive attack that can overwhelm the system.

Amazing – my Dad is one of the first test subjects on this drug. We were at the end with no remaining options bur a marrow transplant. ABT-199 has been a life saver. My Dad’s tumor burden has almost vanished. The Doctors tell us the fact that he was so sick and his cancer so unresponsive may have been a positive in protecting him from TLS. Again, amazing.

So interesting. I have been in this trial for just over a year. At the beginning of the trial my bone marrow showed 67% leukemic cells now my marrow is .03% leukemic cells. All my other blood lines are in great shape with the exception of my platelets hovering at 108. Additionally I have always been treated with allopurinol as part of my pretreatments with Rituxan-single agent, HDMP+Rituxan and FCR as a cautionary step for TLS. A large number of us who are in the ABT199 trials are doing very, very well on this drug. Still, the death of two participants gives good reason to take a hard look at the drug and the processes. Thank you for your article and update.

Comments are closed.