J&J unblind Zytiga phase 3 trial in pre-chemotherapy castrate-resistant prostate cancer

The big cancer news that hit the news wires this morning was not entirely surprising:

“Janssen Research & Development, LLC today announced that it has unblinded the Phase 3 study of ZYTIGA (abiraterone acetate) plus prednisone for the treatment of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) who have not received chemotherapy.”

Source: Press Release

Given the accelerated approval of abiraterone in the post-chemotherapy setting last year, the results in the pre-chemotherapy setting were widely expected to:

- Be even better in earlier stage than the 3.9 months OS advantage already seen

- Likely to have an early study halt

Zytiga already has Compendia listing through mention in the NCCN Guidelines with level 2a evidence in the pre-chemotherapy setting, essentially listed with ketoconazole. Several industry friends with access to market data have mentioned that the pre-chemotherapy share for abiraterone is already around 20-25%, not bad at all given it doesn’t have full approval prior to docetaxel use and has been on the US market less than a year.

Zytiga already has Compendia listing through mention in the NCCN Guidelines with level 2a evidence in the pre-chemotherapy setting, essentially listed with ketoconazole. Several industry friends with access to market data have mentioned that the pre-chemotherapy share for abiraterone is already around 20-25%, not bad at all given it doesn’t have full approval prior to docetaxel use and has been on the US market less than a year.

No clinical details were provided by the Data Science Monitoring Committee (DSMC), but the data are expected to be presented at a clinical meeting later this year (Adam Feuerstein of The Street speculated that ASCO was a likely target). I do hope so, but that would suppose an abstract was sent in with no data by the late breaking deadline of Feb 1st.

The company did state that:

“The company plans to submit for regulatory approval in the United States and around the world beginning in the second half of 2012.”

At this rate, J&J should receive the new indication in the first half of 2013, based on the 302 trial data, depending on whether the filing is accepted as an accelerated, priority or regular review. No doubt this information will be apparent after filing has taken place.

One challenge with early stoppage of trials based on progression-free survival (PFS) is that determining whether patients truly live longer, as judge by overall survival (OS), becomes much more difficult, if not impossible. Once patients on placebo are offered the active drug, there is a crossover effect confounding any subsequent data analysis.

The news today will impact several other companies in the advanced prostate cancer landscape

Medivation and Astellas are expected to file MDV3100 in the post chemotherapy setting soon based on the phase 3 AFFIRM study. This agent has several attractive advantages over abiraterone in that:

- no concomitant prednisone or steroid administration is required (hence less puffiness and related side effects) and

- it targets splice variants as well as the AR, which may lead to less drug resistance.

Based on the post-chemotherapy data we’ve seen so far (MDV3100 saw a slightly longer improvement in OS, which may be related to the above), we can expect that the phase III PREVAIL trial prior to docetaxel to also show a similar trend to the Zytiga study. It won’t surprise me at all if the interim analysis also leads to the DSMC recommending early unblinding. Based on the Zytiga data, it wouldn’t surprise me if the interim analysis for MDV3100 came up as early as mid next year, which would be earlier than expected.

Two drugs that will be impacted by these developments with hormonal agents are Dendreon’s Provenge, which is approved prior to docetaxel and Sanofi’s Jevtana (cabazitaxel), which is approved after docetaxel.

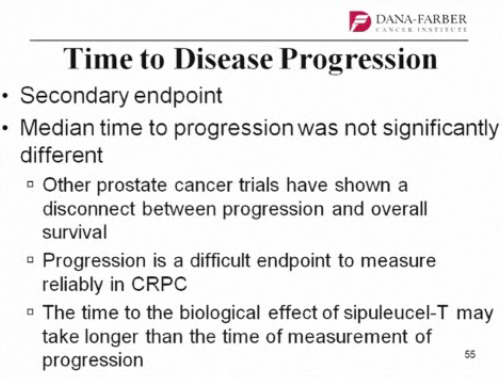

The immunotherapy sipuleucel-T (Provenge) is an unlikely partner for combination with abiraterone given that steroids suppress the immune system, while many older men with metastatic would much rather take a pill than undergo the debilitating side effects of myelosuppressive cytotoxics such as the taxanes. Certainly my Dad was in that category, as are many men in their 70’s. Once approved, Alpharadin (radium-223) may well offer a useful option for that subset of patients, especially of they have already tried ADT and seen biochemical relapse with rapidly rising PSA levels. Provenge is likely to be negatively impacted by Zytiga approval pre-chemotherapy.

Approval of Zytiga in the pre-chemotherapy setting will likely increase its share there, since many oncologists are somewhat sceptical about Provenge in terms of how it works, how effective it is, how to monitor patient progress on it (it doesn’t seem to affect pain, PSA or any of the usual markers of disease) and the hefty price tag ($93K for 3 infusions) doesn’t help either. MDV3100 would likely have an even stronger impact, since urologists dislike using steroids and managing the complications, plus Astellas have a solid franchise in urology already.

At this rate, Jevtana will be pushed further out down the treatment paradigm and reserved for salvage therapy in the younger, fitter patients. Its biggest challenge is competing with it’s fellow taxane, docetaxel, since many oncologists will re-challenge with the generic if the patient previously did well on it. Any delay (through improved survival with newer, earlier treatments) will delay time to cabazitaxel uptake. This will likely get worse once MDV3100 is approved, and oncologists can sequence them.

At what point will we see placebo trials go away?

I’m not a big fan of placebo-controlled trials, except where there are no standard of care or alternative clinical options for patients. Until recently, the advanced prostate cancer market was relatively immature with few approved therapies, so placebo trials were de rigeur. Going forward though, new entrants to the market will face the ethical dilemma of how can placebo-controlled trials be justified in a market where drugs such as abiraterone (or MDV3100 and Alpharadin, if approved) have a proven survival advantage? It will push the bar for new market entries higher (and more costly). Millennium’s TAK-700 (orteronel), which is similar to abiraterone but may or may not need steroids, may well have just made it into clinical trials in time before that window shuts off.

And finally…

The good thing is that after a decade of not much happening in the advanced prostate cancer market, we are seeing a lot if new therapies, often with different mechanisms of action, being developed for this disease. There are others I haven’t mentioned here, including custirsen (Oncogenex) and cabozantinib (Exelixis) which are also undergoing clinical trials and we await those results too.

As more drugs for castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) are approved, sequencing and combinations will also come to the fore to determine optimal strategies for improving outcomes for men with prostate cancer. It’s an exciting market to be following given the rapid progress over the last year or so, but hopefully, this is just the beginning and there will be much more yet to come.