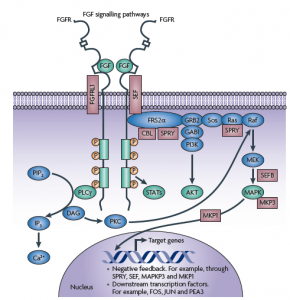

PI3-kinase inhibition is becoming quite a hot topic in cancer research – for those of you interested in learning about the compounds in this area, you can find out more from previous posts here and here as background information before reading the summary of the latest research below.

A friend kindly alerted me to a new article by Donev et al., (2011) that discussed how PI3K inhibition can potentially overcome resistance associated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in EGFR mutated lung cancer. This is an important area in both cancer research and in the clinic, because while erlotinib and gefitinib have been approved for the treatment of lung cancers where the EGFR mutation is present, efficacy is usually limited by the development of drug resistance.

There are a number of reasons for the development of resistance with EGFR inhibitors:

- Pao et al., and Kobayashi et al., (2005) demonstrated that acquired resistance can be due to a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain, ie T790M.

- Engleman et al., (2007) observed that MET gene amplification is also an important mechanism for driving resistance by activating ERBB3 Signaling.

- Yano et al., (2008) demonstrated the importance of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) inducing gefitinib resistance of lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR-activating mutations by activating MET, which restores phosphorylation of downstream MAPK-ERK1/2 and PI3K-Akt pathways.

The role of MET and HGF in EGFR mutations is an interesting one. Turke et al., (2010) subsequently demonstrated that MET activation by its ligand, HGF, also induces drug resistance through GAB1 signaling. HGF accelerated the development of MET amplification both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, EGFR resistance, due to either MET amplification or autocrine HGF production, was “cured in vivo by combined EGFR and MET inhibition.” Now, I don’t normally like the use of the word ‘cure’ but it did get my attention! What was clear from their data was that rare MET-amplified cells exist in some EGFR-mutant lung cancers before, treatment. This suggests that HGF is able to accelerate MET amplification by expanding the preexisting MET-amplified cells.

Kasahara et al., (2010) did some research looking at serum HGF and found that it was strongly related to the outcome of EGFR-TKIs treatment. It would therefore be interesting to develop the idea further to determine if the approach could be used to refine the selection of patients expected to respond to EGFR-TKIs treatment.

A more recent paper by Donev et al., (2011) takes the HGF resistance idea further. They demonstrated that transient blockade of PI3K-Akt pathway by PI3K inhibitor and gefitinib could overcome HGF-mediated resistance to EGFR-TKIs by inducing apoptosis in both in vitro and in vivo models. This approach may be particularly useful in those patients who develop acquired resistance to EGFR therapy driven by HGF.

Impact of the translational research findings:

Of course, we don’t yet know how all this body of research will translate into the clinic in humans, but these recent findings do begin to give us some pointers of where to begin. Based on the research to date, I don’t think it’s going to be as simple as adding a PI3K or MET inhibitor into the mix with an EGFR TKI in every patient though.

A logical and smart approach would be to categorise patients into several groups and determine treatment according to the tumour characteristics:

- those who are MET amplified upfront (i.e. MET high vs MET low)

- those with a T790M mutation present or develop one during treatment

- those who develop HGF-acquired resistance

There are some T790M inhibitors in very early development, but most of these seem to have languished in pipelines to date. I do recall that Pfizer had one in development (PF00299804), based on a paper by Engleman et al., (2007). However, I have not heard much about it lately, probably because they have a large oncology pipeline and are focusing on getting crizotinib to market in advanced lung cancer with ALK translocations.

Boehringer have pan ERB agent in the clinic, BIBW 2992, in newly diagnosed patients as a single agent, but it is too early to tell how effective it will be. Sometimes being first into the clinic isn’t always the best approach, because others slightly behind can take advantage of new research findings and design smart combination trials based on the translational findings.

MET inhibitors are much more common and a number of pharma companies are looking at these in phase II or III trials in combination with erlotinib in lung cancer. The most advanced are ArQule’s ARQ-197 and Roche’s MetMAB, both of which had data presented at ESMO last autumn. Roche showed clear differences in response to MetMAB in patients segmented for MET high vs MET low expression. In contrast, ArQule reported the data in the aggregate at ESMO, so it wasn’t as easy to see what was happening from a biomarker perspective. They also announced that they have accrued the first patient in their phase III trial earlier this month so it will be a little while before we hear how successful these two compounds will be.

PI3-kinase inhibitors are much more plentiful and include BEZ-235 (Novartis) and GDC-0941 (Roche) amongst many others, some of which I previously discussed last year. These may have a role to play in HGF-mediated EGFR resistance, for example, where the current translational data suggests that adding a PI3K inhibitor may be an effective strategy to pursue.

Meanwhile, on the HGF front, Okamoto et al., (2010) reported that preclinical results with TAK-701 (Takeda/Millennium), a humanized monoclonal antibody to HGF. They found that it reversed gefitinib resistance induced by tumor-derived HGF in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with an EGFR mutation in a human lung cancer cell model. These results are encouraging and give some clues of where to start in the clinic with this compound in combination with an EGFR inhibitor.

Overall, this field is looking very promising, but it will be very important to carefully translate the translational research findings into different patient subsets in clinical trials associated with EGFR mutated NSCLC and EGFR TKIs.

References:

Pao, W., Miller, V., Politi, K., Riely, G., Somwar, R., Zakowski, M., Kris, M., & Varmus, H. (2005). Acquired Resistance of Lung Adenocarcinomas to Gefitinib or Erlotinib Is Associated with a Second Mutation in the EGFR Kinase Domain PLoS Medicine, 2 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073

Kobayashi, S., Boggon, T., Dayaram, T., Jänne, P., Kocher, O., Meyerson, M., Johnson, B., Eck, M., Tenen, D., & Halmos, B. (2005).

Mutation and Resistance of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer to Gefitinib

New England Journal of Medicine, 352 (8), 786-792 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238

Engelman, J., Zejnullahu, K., Mitsudomi, T., Song, Y., Hyland, C., Park, J., Lindeman, N., Gale, C., Zhao, X., Christensen, J., Kosaka, T., Holmes, A., Rogers, A., Cappuzzo, F., Mok, T., Lee, C., Johnson, B., Cantley, L., & Janne, P. (2007). MET Amplification Leads to Gefitinib Resistance in Lung Cancer by Activating ERBB3 Signaling Science, 316 (5827), 1039-1043 DOI: 10.1126/science.1141478

Yano, S., Wang, W., Li, Q., Matsumoto, K., Sakurama, H., Nakamura, T., Ogino, H., Kakiuchi, S., Hanibuchi, M., Nishioka, Y., Uehara, H., Mitsudomi, T., Yatabe, Y., Nakamura, T., & Sone, S. (2008). Hepatocyte Growth Factor Induces Gefitinib Resistance of Lung Adenocarcinoma with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Activating Mutations Cancer Research, 68 (22), 9479-9487 DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1643

Turke, A., Zejnullahu, K., Wu, Y., Song, Y., Dias-Santagata, D., Lifshits, E., Toschi, L., Rogers, A., Mok, T., & Sequist, L. (2010). Preexistence and Clonal Selection of MET Amplification in EGFR Mutant NSCLC Cancer Cell, 17 (1), 77-88 DOI: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.022

Kasahara, K., Arao, T., Sakai, K., Matsumoto, K., Sakai, A., Kimura, H., Sone, T., Horiike, A., Nishio, M., Ohira, T., Ikeda, N., Yamanaka, T., Saijo, N., & Nishio, K. (2010). Impact of Serum Hepatocyte Growth Factor on Treatment Response to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Adenocarcinoma Clinical Cancer Research, 16 (18), 4616-4624 DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0383

Okamoto, W., Okamoto, I., Tanaka, K., Hatashita, E., Yamada, Y., Kuwata, K., Yamaguchi, H., Arao, T., Nishio, K., Fukuoka, M., Janne, P., & Nakagawa, K. (2010). TAK-701, a Humanized Monoclonal Antibody to Hepatocyte Growth Factor, Reverses Gefitinib Resistance Induced by Tumor-Derived HGF in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with an EGFR Mutation Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 9 (10), 2785-2792 DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0481

Donev, I., Wang, W., Yamada, T., Li, Q., Takeuchi, S., Matsumoto, K., Yamori, T., Nishioka, Y., Sone, S., & Yano, S. (2011). Transient PI3K Inhibition Induces Apoptosis and Overcomes HGF-mediated Resistance to EGFR-TKIs in EGFR Mutant Lung Cancer Clinical Cancer Research DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1993

Engelman, J., Zejnullahu, K., Gale, C., Lifshits, E., Gonzales, A., Shimamura, T., Zhao, F., Vincent, P., Naumov, G., Bradner, J., Althaus, I., Gandhi, L., Shapiro, G., Nelson, J., Heymach, J., Meyerson, M., Wong, K., & Janne, P. (2007). PF00299804, an Irreversible Pan-ERBB Inhibitor, Is Effective in Lung Cancer Models with EGFR and ERBB2 Mutations that Are Resistant to Gefitinib Cancer Research, 67 (24), 11924-11932 DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1885