Early this morning I saw a headline float by my Twitter stream from yesterday with a link to an article or paper suggesting that yes, we can indeed predict metastasis. I can’t remember who shared it, or what was the exact news article but a quick Google search for latest news found some noise around a potential biomarker, CPE-ΔN. The paper (open access) in the references link below, is from the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Now, the idea that a biomarker might be able to predict metastasis is important because it signals the need for more aggressive treatment as the disease is advancing. Equally, if someone is doing well, you don’t want to intensify therapy needlessly but resection may be more appropriate. Clearly, the earlier you detect the cancer, the better, but conversely, figuring out when to change treatment and prevent or slow metastasis is also important.

Reading the paper carefully, the authors stated:

“We report here that the carboxypeptidase E gene (CPE) is alternatively spliced in human tumors to yield an N-terminal truncated protein (CPE-ΔN) that drives metastasis.”

In the research, they used a liver cancer model (or hepatocellular cancer, HCC) to see what was happening with the protein. Interestingly, CPE-ΔN tended to be present and have high levels in tumours that have metastasised.

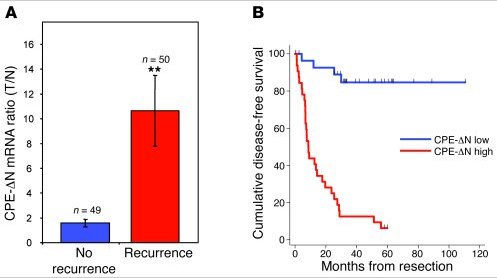

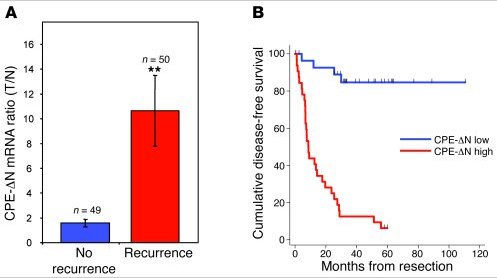

They followed a group of patients with HCC (n=99) and looked to determine whether high or low levels of CPE-ΔN was associated with prognosis, with interesting results:

They also looked at patients with stage 2 disease that had only spread within the liver, as well as patients with a rare adrenal disease and colon cancer. The patients with stage II HCC have a low chance of recurrence, but it can happen, so the question was could the biomarker be used to predict those most at risk?

The answer was yes.

Of the patients with early HCC (n=18):

- Thirteen had low levels of CPE-ΔN and 10 of those were still cancer-free three years after surgery. However, three with low CPE-delta N levels did have recurrence, giving an accuracy level of 77% in predicting metastasis.

- Five had high levels of CPE-ΔN and in four of them recurrence occurred, giving an accuracy level of 90%.

All in all, it’s a good piece of solid research that may have important implications for future research. Be warned, the paper is a little heavy to read though!

The next steps for the group are:

- Find a therapeutic method of blocking CPE-ΔN, preferably with a small molecule

- Determine the mechanism by which CPE-ΔN is activated, thereby figuring out how the switching on of metastasis works

All in all, although this research, while still at the very early stage, looks promising and worth following to see how the idea pans out. I can’t help wondering how this research will impact the Norton and Massagué cancer seeding theory – it should add to it. Now, if only we can find out what activates the CPE-ΔN protein, thereby triggering the metastasis, that could well be a key piece in the puzzle.

References:

Lee, T., Murthy, S., Cawley, N., Dhanvantari, S., Hewitt, S., Lou, H., Lau, T., Ma, S., Huynh, T., Wesley, R., Ng, I., Pacak, K., Poon, R., & Loh, Y. (2011). An N-terminal truncated carboxypeptidase E splice isoform induces tumor growth and is a biomarker for predicting future metastasis in human cancers Journal of Clinical Investigation DOI: 10.1172/JCI40433

Lee, T., Murthy, S., Cawley, N., Dhanvantari, S., Hewitt, S., Lou, H., Lau, T., Ma, S., Huynh, T., Wesley, R., Ng, I., Pacak, K., Poon, R., & Loh, Y. (2011). An N-terminal truncated carboxypeptidase E splice isoform induces tumor growth and is a biomarker for predicting future metastasis in human cancers Journal of Clinical Investigation DOI: 10.1172/JCI40433

![]() Mullard, A. (2011). 2010 FDA drug approvals Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 10 (2), 82-85 DOI: 10.1038/nrd3370

Mullard, A. (2011). 2010 FDA drug approvals Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 10 (2), 82-85 DOI: 10.1038/nrd3370