Effectively targeting KRAS in lung cancer with a MEK inhibitor

Today is the 1000th blog post here on PSB, a milestone I never imagined actually reaching while writing the inaugural and rather boring post way back in 2006. At that time, 10 posts seemed a lot, never mind 100 or 1000! Anyway here we are, thus the facing the new dilemma of what to write about to celebrate the event.

The nice thing about having a following on Twitter is a ready supply of suggestions and papers from readers. Today’s suggestion comes from Angela Alexander (@thecancergeek), a Post Doc in breast cancer research at MD Anderson who asked if I had seen the exciting new phase II data on MEK inhibition in lung cancer from Pasi Janne’s lab. I’ve long been an admirer of his work, so it is fitting the data has just been published in Lancet Oncology this week (reference below).

Background on KRAS in lung cancer:

KRAS is a particularly tricky gene target because some tumours are seriously addicted to this oncogene, making it tough to completely shutdown from a pathway perspective. Part of the reason is that few drugs possess sufficient therapeutic index and thus resistance can occur fairly early. Recently, though, a number of companies have been exploring targeting downstream of KRAS to see if that approach could attentuate the driver activity in some way. One of these targets is MEK, which many of you will be familiar with in metastatic melanoma, where MEK inhibitors have been shown to be an effective strategy in combination with BRAF inhibitors to produce improved outcomes.

KRAS has been found to be abnormal, or mutated, in approx. 20-25 percent of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), making it the most frequent of the mutations seen in this disease. We also know that KRAS mutations predict a poor response to EGFR inhibitors and are a negative prognostic indicator. Finding therapeuetic strategies to overcome KRAS are therefore a high priority in clinical research.

What is the latest study about?

Janne et al., (2012) performed a simple but elegant phase II study looking at the impact of adding a MEK inhibitor, selumetinib (AZD6244/ARRY-142886) from AstraZeneca and Array to standard chemotherapy, docetaxel (Taxotere) to determine whether targeting KRAS indirectly would impact overall survival (OS) and allow patients to live longer. Selumetinib targets both MEK1 and MEK2 and previous phase I trials suggested a promising safety and efficacy profile to warrant further investigation.

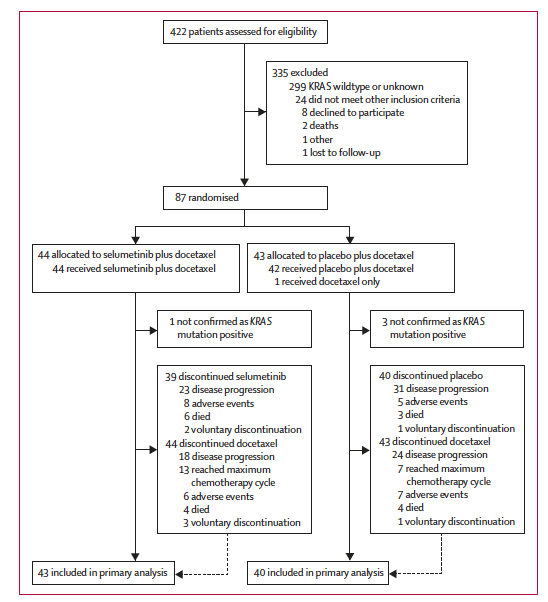

To get an idea of the complex logistics involved in the study, 422 patients were screened from 67 sites in 12 countries, of whom 87 whom previously received initial chemotherapy and had both NSCLC AND the KRAS mutation were selected to participate in the trial, indicating an incidence of 20.1% for KRAS-positivity in this sample:

Source: Jänne et al., (2012)

Half the sample (n=44) were randomised to receive standard docetaxel chemotherapy (75 mg/m2 q3w) plus selumetinib capsules (75 mg BD) and the other half (n=43) received docetaxel plus placebo. Both groups were treated until progression or toxicities were unacceptable. Subsequent therapies were allowed, but not crossover.

The primary endpoint for this study was OS and secondary endpoints included PFS, objective response and others such as safety.

What did they find?

Now, first up I would expect the docetaxel alone group to have an overall survival in the second-line setting of around 5-6 months. In this trial the MOS for the placebo group was 5.2 months, which is in line with expectations. However, the selumetinib arm had a near doubling in MOS to 9.4 months, which I think is quite impressive in a very difficult to treat subgroup. PFS also saw a doubling from 2.1 months in the docetaxel alone group to 5.3 months in the docetaxel plus selumetinib group.

Toxicities appeared to be in line with previous trials – selumetinib tends to increase grade 3/4 events when combined with docetaxel i.e. neutropenia (67%) compared to the docetaxel alone group (55%), febrile neutropenia (18% vs. 0%) and asthenia (9% vs. 0%).

What can we conclude from this study?

I thought these results were very promising, although of course, the caveat is that it’s early days yet and a larger phase III multi-center trial is needed as a confirmatory study – not all phase II trials will yield positive data once they complete phase III so we cannot project that far yet. The main added toxicity, myelosuppresion, is to be expected given that it is likely additive to the existing effect seen with docetaxel alone.

This is, however, the first time I can recall seeing very solid evidence that adding a MEK inhibitor to standard chemotherapy in second-line NSCLC significantly improved overall survival in patients with KRAS mutations.

Overall, these results are encouraging and definitely warrant a phase III confirmatory trial with docetaxel and selumetinib in the second-line setting for NSCLC patients with the KRAS mutation.

References:

![]() Jänne, P., Shaw, A., Pereira, J., Jeannin, G., Vansteenkiste, J., Barrios, C., Franke, F., Grinsted, L., Zazulina, V., Smith, P., Smith, I., & Crinò, L. (2012). Selumetinib plus docetaxel for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study The Lancet Oncology DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70489-8

Jänne, P., Shaw, A., Pereira, J., Jeannin, G., Vansteenkiste, J., Barrios, C., Franke, F., Grinsted, L., Zazulina, V., Smith, P., Smith, I., & Crinò, L. (2012). Selumetinib plus docetaxel for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study The Lancet Oncology DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70489-8

One of the most interesting highlights of this ESMO for me has actually not been some new data or science that was presented here, but the sense of anticipation about the forthcoming nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane) data in pancreatic cancer.

One of the most interesting highlights of this ESMO for me has actually not been some new data or science that was presented here, but the sense of anticipation about the forthcoming nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane) data in pancreatic cancer.

Following on from my preview of the

Following on from my preview of the  This week I’m attending an interesting 2-day conference on PI3K at the New York Academy of Sciences (NYAS).

This week I’m attending an interesting 2-day conference on PI3K at the New York Academy of Sciences (NYAS). It’s been a crazy busy time since the

It’s been a crazy busy time since the