After a number of basic research and science sessions over the last two days (see the Update 1 post on the science that intrigued me for more details), but the last two days heralded some excellent clinical sessions, in both oral and poster forms. These included the presentation of the much anticipated update to the BOLERO-2 trial, which was also published in the New England Journal of Medicine online and the CLEOPATRA study, also published in the same journal. One of the more impressive posters that caught my eye was the ENCORE 301 study, which provided an update to the entinostat data in ER/PR+ HER2- advanced breast cancer.

Many of you will have read the wire and news articles released in a barrage on Wednesday evening with the NEJM publications ahead of the presentations on Thursday and Friday, but I wanted to put them in context of what we know so far and why these studies are both elegant and important.

Why am I fascinated by these particular studies?

Drug resistance can develop either upfront or is acquired in response to treatment over time. The latter is also known as adaptive resistance, as the tumour evolves certain strategies to ensure it’s survival. This is one reason why many people will have a different response to the same treatment.

In simple terms, if we can figure out ways to:

- Either delay the development of resistance up-front in treatment naive patients by enabling more comprehensive pathway suppression

- Or switch to a new logical combination regimen once resistance has developed

then we may be able to prolong patient outcomes and survival further. To me, these kind of rational approaches make much more sense than merely throwing random chemotherapy doublets of choice at the problem. These two strategies are very much at the heart of the three impressive studies mentioned above. Let’s look at them in a little more detail.

BOLERO2

BOLERO-2 is the acronym for the breast cancer trials of oral everolimus and the updated safety and efficacy data were reported here at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), although it should be noted that the NEJM article is based on the phase III ECCO data previously presented by Jose Baselga in September.

The trial design, though, remains the exactly same – patients were randomised to receive with everolimus plus exemestane versus placebo plus exemestane to determine whether the mTOR added anything to the AI alone.

The rationale behind this trial is that mTOR is a known cause of resistance to AI therapy, so the combination targets both the ER, which is driving the tumour proliferation, and mTOR targets the adaptive resistance pathway. Shutting down both pathways should lead to improved survival, which we clearly saw at ECCO (6.5 months extra survival as measured by PFS).

The latest data presented by Dr Gabriel Hortobaygi (MDACC) confirmed that the responses continue to be durable, with an improvement in the PFS with the combination arm now up to 11.0 months, up from 10.6 months at ECCO. The results for the exemestane control arm remained the same at 4.1 months. This means that the improvement in survival with the mTOR now offers a median 6.9 months extra benefit. OS had not yet been reached and therefore was not reported.

My view? These are excellent results from a well designed trial with a logical and elegant design given that we know mTOR is one of the adaptive resistance mechanisms to AI therapy and confirm that the original hypothesis was a valid one.

That said, what we don’t know is who will most benefit from the combination i.e. which women are more likely to respond. I’d love to know whether the really good responders had higher mTOR levels or overexpression or whether there is something else that would help us determine the likely responders for several reasons:

- mTOR isn’t the only acquired resistant pathway to AI – there are others – so hopefully a way to determine who would be the ideal candidate for mTOR therapy will emerge from retrospective analysis.

- A quarter (26%) of both arms received prior chemotherapy – did these women do better or worse when given the AI-mTOR combination compared with those who only received hormonal therapies?

- This combination will not be cheap, considering the likely costs of everolimus alone without the AI could easily be ~$7K/month and the cost of exemestane must be added to that.

These points aside, I do think these results are impressive and good news for an advanced population of women who may not want to even consider chemotherapy – the current data suggests that many will get more time with this approach. Expect to see Novartis filing for everolimus approval in advanced breast cancer with the FDA before the year is out.

ENCORE 301

In the same patient population of ER/PR+ HER2- women, there was an update to the phase II ENCORE 301 trial with the HDAC inhibitor, entinostat, that we blogged in more detail at the recent AACR Molecular Targets meeting.

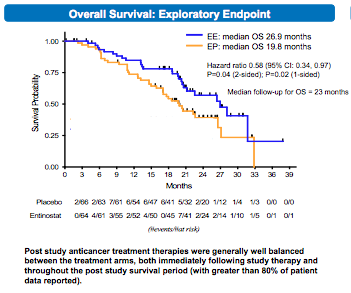

What was new about the data here was an update on the overall survival (OS) data. Remember, in San Francisco the PFS for the entinostat arm (comparable to the everolimus-exemestane arm in BOLERO2) was 8.5 months in the women with high acetylation, an excellent predictive biomarker of response.

Now, I was wondering why the OS has still not yet been met in the BOLERO2 trial here and realised why with the updated entinostat data:

As you can see above, based on a medium follow-up of 23 months, the OS has improved in these patients in the phase II trial from 19.8 to 26.9 months, an improvement of 7.1 months of life.

We’ve all seen so many trials where the benefit is a mere 1-3 months, so to see several trials in advanced breast cancer where the survival is measured in 6-7 months is breathtaking. Long may this trend continue with more rationally designed combinations and robust trial designs!

The entinostat phase II data certainly provides a good efficacy and safety signal to continue development and I was delighted to see that Syndax are moving forward to a confirmatory phase III trial in 2012. I’m very much looking forward to watching how this study progresses, although we obviously won’t know the results for a while.

CLEOPATRA

The CLEOPATRA study looks at a completely different patient population than BOLERO and ENCORE. In this situation, it’s looking at women were treatment naive, not refractory, who also needed to be HER2+ to enter the study.

As discussed in the What’s Hot at SABCS review prior to the meeting, pertuzumab is similar to trastuzumab in that it is a monoclonal antibody to HER2, but also differs in that it acts in a different part of the HER domain from Herceptin and also prevents pairing of HER2 and 3 dimersiation:

HER dimerization, source: NEJM

The idea behind combining pertuzumab and trastuzumab upfront is to enable a more comprehensive shutdown of the HER2 pathway and delay the resistance setting in. By doing this, PFS should increase.

Dr Jose Baslega presented the results of the CLEOPATRA trial for the first time to a packed and highly excited audience in San Antonio. Unfortunately, I wasn’t there as I was en route to the American Society of Hematology (ASH) meeting, but like many, I was eagerly reading the tweets and reactions from the attendees.

The Roche press release summed up the essence of the data nicely:

“The median PFS improved by 6.1 months from 12.4 months for Herceptin and chemotherapy to 18.5 months for pertuzumab, Herceptin and chemotherapy.

Overall survival (OS) data are currently immature, with a trend in favour of the pertuzumab combination.”

In short, another stunning six month leap in survival in an entirely different patient population of advanced breast cancer. This is the sort of data those of us working in the industry live for and hopefully, things will continue to get better because clearly thought leaders such as Martine Piccart (at the the NY Chemotherapy Symposium) and Jose Baselga (at SABCS) are already dreaming and envisioning a world in which women with HER2+ breast cancer can be treated without chemotherapy at all. Now that would be a wonderful thing indeed and I really hope to see it happen sooner rather than later.

One thing that hasn’t been factored into the equation is the antibody drug conjugate T-DM1 and how that relates to pertuzumab and trastuzumab. The phase III trial MARIANNE is currently enrolling patients and may offer us an answer to that question in a couple of years time.

For those of you interested in some expert commentary, the NEJM published an excellent editorial from Dr William Gradisher (Northwestern, Chicago) accompanying the BOLERO2 and CLEOPATRA studies which is well worth reading (see references below).

In summary…

These three studies all show how rationally designed and elegant studies based on solid science can lead to large leaps in improvement in survival in the clinical setting. Roche have already filed the BLA for pertuzumab and Novartis are expected to file everolimus in advanced breast cancer soon. Syndax are already planning their phase III trial for entinostat.

It’s a very good period for ER/PR+ HER2- and HER2+ advanced breast cancers – from that perspective, this year’s San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium was very uplifting and one of the more exciting meetings of the last five years.

References:

Baselga, J., Campone, M., Piccart, M., Burris, H., Rugo, H., Sahmoud, T., Noguchi, S., Gnant, M., Pritchard, K., Lebrun, F., Beck, J., Ito, Y., Yardley, D., Deleu, I., Perez, A., Bachelot, T., Vittori, L., Xu, Z., Mukhopadhyay, P., Lebwohl, D., & Hortobagyi, G. (2011). Everolimus in Postmenopausal Hormone-Receptor–Positive Advanced Breast Cancer New England Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653

Baselga, J., Campone, M., Piccart, M., Burris, H., Rugo, H., Sahmoud, T., Noguchi, S., Gnant, M., Pritchard, K., Lebrun, F., Beck, J., Ito, Y., Yardley, D., Deleu, I., Perez, A., Bachelot, T., Vittori, L., Xu, Z., Mukhopadhyay, P., Lebwohl, D., & Hortobagyi, G. (2011). Everolimus in Postmenopausal Hormone-Receptor–Positive Advanced Breast Cancer New England Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653

Baselga, J., Cortés, J., Kim, S., Im, S., Hegg, R., Im, Y., Roman, L., Pedrini, J., Pienkowski, T., Knott, A., Clark, E., Benyunes, M., Ross, G., & Swain, S. (2011). Pertuzumab plus Trastuzumab plus Docetaxel for Metastatic Breast Cancer New England Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216

Gradishar, W. (2011). HER2 Therapy — An Abundance of Riches New England Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe1113641

![]() O’Hagan, H., Wang, W., Sen, S., DeStefano Shields, C., Lee, S., Zhang, Y., Clements, E., Cai, Y., Van Neste, L., Easwaran, H., Casero, R., Sears, C., & Baylin, S. (2011). Oxidative Damage Targets Complexes Containing DNA Methyltransferases, SIRT1, and Polycomb Members to Promoter CpG Islands Cancer Cell, 20 (5), 606-619 DOI: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.012

O’Hagan, H., Wang, W., Sen, S., DeStefano Shields, C., Lee, S., Zhang, Y., Clements, E., Cai, Y., Van Neste, L., Easwaran, H., Casero, R., Sears, C., & Baylin, S. (2011). Oxidative Damage Targets Complexes Containing DNA Methyltransferases, SIRT1, and Polycomb Members to Promoter CpG Islands Cancer Cell, 20 (5), 606-619 DOI: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.012

Source: Dr Susan O’Brien ASH 2011 CLL oral session, reprinted with permission

Source: Dr Susan O’Brien ASH 2011 CLL oral session, reprinted with permission