For as long as anyone can remember, humanity has wondered, “Why do we do things even when we know we should not?”

James Shelley, Caesura Letters

Akrasia is a rather common affliction in Pharma and Biotech. After all, why do so many companies fall into the deathly trap of running generic catch-all studies in heterogeneous cancers without an oncogenic target or validated biomarker? Or even specific, well defined subsets to improve the homogeneity ratio? Or perhaps they knowingly underpower a randomized trial for overall survival?

The list goes on…

Later, senior executives predictably scratch their heads bemusedly when the results come in — and they’re not what they hoped for, or were expecting. No one stopped to ask the obvious question – how can you hit a target you don’t have?

A head-desk kind of moment to be sure.

Hope is not a viable strategy in this business. It’s simply too expensive to shackle the odds against you in the face of intelligent analysis or solid evidence.

That said, rather than rant about this (again), I wanted to take a look and explore R&D and oncology drug development in a more positive light. There are plenty of succeses that have either made it to market or are very close in phae III development in oncology and hematology. It’s always a pleasure to find enlightened and intelligent souls in this realm, people with clarity of vision and a driving passion to get things done right.

I was really thrilled to meet one such person at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) meeting in New Orleans recently in person.

Dr Carol Gallagher, the former CEO of Calistoga and now VC Partner at Frazier Healthcare was truly a delight to chat with. Many of you will recall the stunning early data for what was then CAL-101 (now idelalisib), a PI3K-delta inhibitor in hematologic malignancies such as B cell lymphomas and leukemias (indolent NHL and CLL). They were the first to demonstrate the proof-of-concept for the target and published early clinical results that got people’s attention.

Dr Carol Gallagher, the former CEO of Calistoga and now VC Partner at Frazier Healthcare was truly a delight to chat with. Many of you will recall the stunning early data for what was then CAL-101 (now idelalisib), a PI3K-delta inhibitor in hematologic malignancies such as B cell lymphomas and leukemias (indolent NHL and CLL). They were the first to demonstrate the proof-of-concept for the target and published early clinical results that got people’s attention.

Rather than describe an interview – it was more like a fireside chat between two people with a similar vision – I wanted to share some of the ideas we discussed in New Orleans. The parallels between our experiences with idelalisib and imatinib were quite striking to me… From the central focus on the science and the patients, to the carefully thought out clinical program development etc… only to end up with a sudden realisation that you’ve both gone through similar experiences, with an identical philsophy; “what you too?!” is both pleasant and unnerving at the same time!

Pharma Strategy Blog: One of the things that I was interested to learn is what is your general philosophy with R&D? Strategically, what are you trying to accomplish?

Dr. Gallagher: I think we are at a moment in time that I feel fortunate to be part of where the last 20 to 30 years, we’ve had a much better molecular understanding of what drives the cancer cell. What I’m particularly fascinated with is I think we’re getting even more of an understanding of how that cancer cell is interacting with its environment and the immune system and, of course, as evidenced by PD-1 and the PD-L1, it’s fascinating to now think about that interaction. This has given us a lot of opportunities to think about specific molecular targets that could be drugable, and that could be either a small molecule or antibody, depending on, of course, where the target is, and how we’re thinking about drugging it. That (concept) has changed everything, because we can be more specific in our targeting versus giving people poison.

I think that it’s certainly an efficacy story, but it’s actually a quality of life story. I don’t mean by that registrationable endpoint of quality of life, but I do mean it in the sense of when you’re diagnosed with cancer, don’t you want to try to find a way to manage that disease, but in a way where you could still see your grandchildren or make your daughter’s high school graduation? Certainly, chemotherapy agents have been quite effective. In breast cancer, where it’s a very chemo-responsive disease, it’s hard to imagine that it’s completely going away, but can we find opportunities to give patients therapies that might be more consistent with a good life experience as well as treating their disease?

I was fortunate, for a brief amount of time in my career at Agouron to actually work in the HIV space in those early days of HIV treatment and the protease inhibitors. That was what enabled new products to come very quickly and take over space was that the opportunity to improve the adverse event profile was significant, even though, of course, just even getting the disease treated initially was a major step, but then we were able to actually rapidly, through the industry, improve upon the overall experience for those patients. I think we’re still trying to do that because when you’re living with the disease in a more chronic way, you want to be able to have better therapies.

I have to say the important thing is to focus in on each cancer type because they are all different. I think that the Gleevec example was something we majorly needed for those patients. Now, actually, interestingly, we’re having to manage that, wow, they’re actually living long enough of a time to now have mutations emerge where before, we were just focused on giving them some additional time, and so it’s really great that we’re transitioning.

I saw that too. I worked on Rituxan for a few years at Idec managing that relationship with Genentech, and this was in the early 2000s. What I started to appreciate – that I think has played out in CLL and indolent NHL – is these patients actually do live a fairly long time from the time of diagnosis. It really does matter how much the adverse event profile plays into your life, which is why lots of people would end up choosing single agent Rituxan even though we knew that Rituxan plus chemo would give you more efficacy, but they were choosing no chemo for the quality of life types of aspects of it; again, not meant as a registration endpoint but more of just how you feel every day.

I think that’s where today in R&D, we have to think about the targets but also the patient and their specific disease, and how do we give them true clinical benefit, which is not just efficacy, it’s how do we make their life experience with this disease hopefully better or not so interrupted by having cancer?

Pharma Strategy Blog: I learned that a lot from the Gleevec patients who had advanced. Some of them had six months, if that; maybe some of them had a year. I would go to visit the investigators, and sit in the clinic, and talk to the patients first, and see the PIs at the end. One didn’t want to see them in the middle and get preferential treatment over the patients, but it was a wonderful experience to talk to them, to learn about what is it really like to live with CML or whatever.

Some of them would open up—one lady, she told me she had already booked her funeral! I didn’t know what to say to that and she said, “I want to live long enough to make my daughter’s wedding.” It was six months hence. I found out afterwards from the doctor, “If she gets in the trial, she might live six months. It will be touch and go.” She’s still alive today, and that was 2000, probably 1999/2000, and you start to think about that. Wow, she’s living ten, 11, 12 years for a disease that previously, you had maybe, at the outset, a year.

The other side of this, you don’t necessarily think about at the time, is exactly what you’re saying, is if you turn an acute disease into a chronic one, they have to live with those side effects. We all know the TKIs and antibodies, if you take them for a long period of time, you’re going to have side effects. Some of that aspect of it, and you can see it in CLL with the FCR vs FC or BR in the German trials, where they can argue as long as they like that one is better than the other. But when you look at the side effects and how long patients are getting the side effects, often months afterwards, you can see why patients would choose to take single agent rituximab and feel okay. They might feel a little tired, but they’re not going to get horrible side effects, and I think that’s one of the things that we’re seeing more of in CLL. You can almost imagine with the new CLL11 study that many of these patients with co-morbidities will choose obinutuzunab alone over the combination with chlorambucil, irrespective of the label.

This morning, I went to the ASH press briefing and they had – I still think of it as CAL-101 – they had the idelalisib data, and it looked pretty impressive, but the side effect profile was also, I thought, quite impressive. Patients weren’t having a lot of the dreaded GI effects like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea etc, you could imagine that they’re not distressed and chained to the bathroom. It’s a huge difference.

Dr. Gallagher: Particularly, with that being a patient population where the average age at diagnosis is, I think, 75, and so we’re not talking about a 40-year-old person. We’re talking about a person who likely has other co-morbidities that are challenging for their daily life and to be able to do that.

It was interesting, when we first started thinking about that combination, having worked on Rituxan, I was interested to think about would there be—could idelalisib have enough activity in CLL to be close to a combination that would be R-chemo? That was really our hope, in the sense that then people would have an option—at least earlier in the progression of their disease—that might not be so toxic or causing just daily living skills to not be as easy to do. Is that an opportunity that we actually could see? Of course, the nature of the leukocytosis that is caused where we’re pushing those cells into the blood, we saw early on in the combination work, exploratory work that we did that when you put that with Rituxan, it just cleared everything rapidly. Of course, Rituxan is known that it doesn’t work that well in the lymph nodes in CLL. It is a more peripheral active drug, so it just seemed like an interesting combination to put together.

I have to say my own personal hope was this idea that maybe we could give people a pretty still efficacious option that would then say, “Well, maybe we could wait to do the more toxic things like FCR or even BR.” Bendamustine has its own set of challenges, given that these patients do unfortunately relapse over and over, that could we give them an option? I have to say I was thrilled that the outcome of that trial does actually have a survival benefit even. That makes me believe that we really are going to change the opportunity for those patients to have effective therapy that also allows them to hopefully have a little bit more normal life, not that there aren’t adverse events with these drugs, there certainly are, but I think in comparison, they’re manageable.

Pharma Strategy Blog: I think that one thing that comes down to this meeting, talking to thought leaders and also community oncologists in the poster session, sometimes, we forget that the academic physicians see a lot of younger, fitter, healthier patients because they’ll probably be a little bit more aggressive and educated. They want to live longer, and they’re looking for trials; whereas, in the community setting, they are the 75, 80-year-old patients that you’re talking about.

I’ve heard it so many times from these docs that, “I need something better for my patients. I can’t give them FCR or whatever, they just can’t tolerate it.” Some of them can’t even tolerate bendamustine. They care about their 75 to 80 year old patients, “It’s a big deal, Sally.” We talk about indolent disease, but for them, it’s a different goal of therapy. I do think one of the things that you really start to realize at this meeting is how a whole series of different combinations could evolve, not just idelalisib/Rituxan, but other things in combination.

Dr. Gallagher: Ibrutinib, I think we have a number of very exciting drugs, and I couldn’t be happier that we’ve really started to make some progress, and it is molecularly oriented. It’s really saying these are interesting targets around the B-cell receptor; the AbbVie compound is also very interesting. I feel so excited to be part of what I see is a new era of the dreams that we had over the last ten years are coming to fruition.

Again, it’s not perfect, and we have to keep continuing to strive to do better, but I do hope that these different agents will now offer physicians a whole new tool kit that will let chemo or FC go later into the process, if at all. As you say, 75 to 80, or 75 to 84, there may be other issues that then cause those patients to expire, but in the meantime, they get to their granddaughter’s wedding or things that are real to people.

I have to say, as I have lost my father and have an aging mother, you start to appreciate, I think—and I’m sure physicians, of course, see that with their patients every day—but to appreciate that there are balances of it’s not always just about life extension at any cost because if you’re sick in the hospital with neutropenia (laughter), that’s not actually a very good experience while your family is at home celebrating the holidays.

Pharma Strategy Blog: One of the things a Community oncologist was saying to me yesterday during a session lull was rather interesting. He turned to me and said, “We get obsessed with complete responses and remission!” Then he went on, “I’m thinking about not just the elderly patient, but younger patients. If they get these PRs, and they’re sustained, and they’re durable, and the overall responses are good, and the progression-free survival is good, does it really matter if we don’t achieve a CR?” Now we don’t know the answer yet, but I thought that was a very good question and how the durability plays out will be interesting.

Dr. Gallagher: It’s funny because Langdon Miller, who came and joined us at Calistoga, and was at CTEP earlier in his career, and then at Pharmacia Upjohn, and developed a number of cancer drugs, that was something he talked a lot about when he first came to work with us; that he really thought durable PRs and particularly in these CLL and NHL where to talk about true cure as in most cancers. To talk about true cure, where it’s going away and it’s gone forever, is a difficult thing to achieve. If you’re getting a very durable response where people can live, basically, a fairly normal life for quite a long time, isn’t that like a CR? CRs aren’t always—unfortunately, these patients do relapse, and so it’s not as if we’re talking about a true cure when even we describe CRs in these types of leukemias and lymphomas.

Pharma Strategy Blog: Even if these patients have two to three years on either a single agent or a doublet, and they have a better of quality of life than if they’d had the side effects of FCR, they can still go on to another one with so many choices that we have now.

Dr. Gallagher: Yep, exactly, exactly.

Pharma Strategy Blog: It was interesting that another oncologist in the audience turned to the doc and I and joined in; he chimed in, “Well, you know, I give FCR first line. I give BR second line, and the third line, hmm I put them on a trial for something, or they have pentostatin or whatever they haven’t had.” He felt strongly at the end of it all though, they were really wiped out, and the patients were like, “I don’t think I can take anymore, I’ve had enough. I’d like something just to keep me happy, like a happy pill.” He observed, rather astutely, “We need to think about this differently.”

For the Community oncologists, this is a really critical juncture now. With all these new drugs coming along, in the next probably 12 months, where they have several of new ones available and others coming along in trials, I think it will change the way we monitor these patients and how we look at the disease.

You look at the hematology extremes and you have myeloma at one end, where you have the almost nihilistic Total Therapy, and stem cell transplants and the like, yet 20% of them died from the procedure! Okay, you might have X percent got a cure, but what’s the quality of life after that? Thankfully, in NHL and CLL at the other extreme, we’re moving into an era where there’ll be so many options to hopefully avoid drastic side effects, and it will be really interesting to see where it goes.

Dr. Gallagher: Yeah, I totally agree. I have to say, again, back to my experience of working on Rituxan, is because right before that, as I was talking about it, I was working at Agouron, which became Parke-Davis, Pfizer, and we were working a lot more on the targeted EGFR and then on antiangiogenesis agents. I’d been working more in disease settings like non-small cell lung cancer, where you’re just trying to give them a couple of more months of life.

When I moved over into these indolent diseases and started to really think about, wow, this patient has a number of years, let’s think about how their quality of life matters, it was interesting to me that the physicians themselves, again, back to the single agent Rituxan use, they were, or their patients, someone was recognizing this and making this choice, which from my very academic hat of, well, but we know FCR has a better efficacy percentage, at that time, that data hadn’t been developed. We were still working on it but R-CHOP versus R; we know that that is going to give you a higher response rate of the overall patient population. Why would you ever choose R alone and yet, people were choosing that.

It was such an education where, as you were talking about, you talk to patients, listen to the physicians that are in the Community on the ground outside of Academia, because that balance is very important. I do think that’s one of the things in the United States that’s so interesting is the way that we deliver cancer care is predominantly through the Community and the Academics are certainly very important for advancing research initiatives, but we’re very close to the patient in the United States in the way that we deliver that care. I think we have to keep that balance of listening to what they’re telling us and understanding where there may be opportunities to fill an unmet medical need that might not be quite as Academic as a response rate.

Pharma Strategy Blog: It’s a great time to be in CLL and indolent NHL. I think you’ve been very much a part of that, so I’m really delighted to meet you and hear about the context of what you were trying to do in those early days. It’s certainly coming to fruition now, and that’s really exciting.

Dr. Gallagher: I couldn’t be happier, and it was an amazing team that worked on it. I think the Gilead team has done a great job and will continue with that. There’s some of our Calistoga folks that are part of that Gilead team still, but my hat is off to all the people, all the investigators, the patients. It’s such a great community, and we have to all find a way to work together to advance this, so I really appreciate the time.

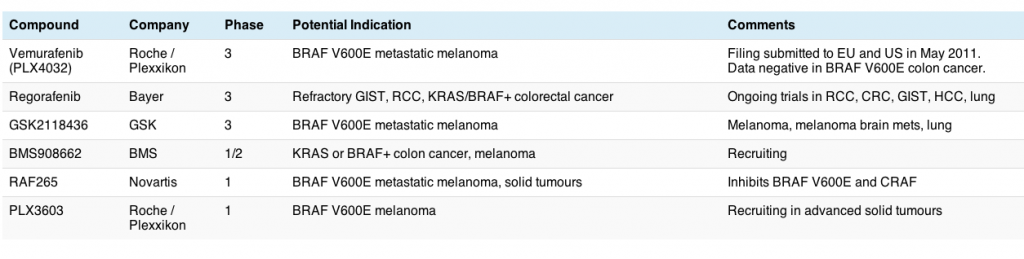

![]() Solit DB, & Rosen N (2014). Towards a Unified Model of RAF Inhibitor Resistance. Cancer discovery, 4 (1), 27–30 PMID: 24402945

Solit DB, & Rosen N (2014). Towards a Unified Model of RAF Inhibitor Resistance. Cancer discovery, 4 (1), 27–30 PMID: 24402945

Last week, brought negative data as

Last week, brought negative data as