Sometimes following the progress of cancer drugs can be very depressing given the failure rate, but every now and then something comes along that really brightens the landscape considerably. This week was one of those times.

Eighteen months ago, I posted a note from the 2010 ESMO meeting regarding GSK’s GSK208436 (now known as dabrafenib) in an early phase I/II trial in brain metastases associated with melanoma that was presented by Dr Georgina Long on behalf of an Australian group.

Do check out that original post – it’s well worth reading for some background context in the light of the new data.

At that time, the data and brain scans were quite simply stunning, but the big unanswered question was how durable would the responses be? After all, many of you will know that people with metastatic melanoma generally have a poor prognosis, with a median overall survival of approximately 9–11 months (see Balch et al., 2009).

Originally, the finding that the drug crossed the blood brain barrier was a surprise, as this MD Anderson press release notes:

“The drug’s activity against brain metastases was initially a serendipitous finding at one study site. In one patient, a research PET scan performed just before starting dabrafenib revealed a brain metastasis, but this result was not available until after treatment began.

The institution’s ethics board approved the patient to continue treatment because a follow-up PET scan two weeks later showed decreased metabolic activity in the brain metastasis and subsequent MRIs showed a reduction in its size.”

This week we learned more about the progress of dabrafenib in brain metastases associated with melanoma from a new publication in The Lancet by the same group, in conjunction with researchers from MD Anderson’s Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics group (see Falchook et al., 2012). This time, the phase I/II data was reported in incurable patients with brain metastases (n=184, 156 of whom also had metastatic melanoma).

The goals of this study were to determine the safety and tolerability, as well as establish a recommended phase II dose in patients.

The most common side effects were in line which those previously reported for BRAFV600 mutant inhibitors:

“The most common treatment-related adverse events of grade 2 or worse were cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma (20 patients, 11%), fatigue (14, 8%), and pyrexia (11, 6%).”

For those of you interested in the recommended phase II dose, the group found that 150mg twice daily was the optimal dose for dabrafenib.

At the initial ESMO presentation in 2010, 9 out of 10 of the patients saw reductions in the overall size of their tumours, so I was most interested to see the latest progress with efficacy in a larger cohort of patients. In this study, the shrinkage continued apace:

“Brain metastases in most patients given dabrafenib reduced in size, with four patients’ metastases completely resolving.”

Emphasis mine. Overall, the phase II portion of the trial demonstrated that the responses continue to look rather encouraging:

“At the recommended phase 2 dose in 36 patients with Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma, responses were reported in 25 (69%) and confirmed responses in 18 (50%). 21 (78%) of 27 patients with Val600Glu BRAF-mutant melanoma responded and 15 (56%) had a confirmed response.

In Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma, responses were durable, with 17 patients (47%) on treatment for more than 6 months.”

I highly encourage reading of the paper for the waterfall plots alone – they are pretty impressive! Overall, nine out of ten patients with brain metastases saw their tumour shrink, as noted in MD Anderson’s press release.

What about the survival curves? So far, the authors have reported the following in the current study:

- Non-brain metastases (n=36): median PFS 5·5 months

- Brain metastases (n=10): median PFS 4·2 months

The authors speculated the reason for the variability in responses may be due to severity of the disease:

“Differences in progression-free survival in patients with varying lactate dehydrogenase concentrations or ECOG performance status suggest that burden of disease could affect response durability.”

Overall survival data was not provided, presumably because they were not yet met, but these early data are very encouraging signs given that few drugs cross the blood brain barrier, leading the authors to conclude:

“Dabrafenib is the first drug of its class to show activity in treatment of melanoma brain metastases. Clinical trials of melanoma usually exclude patients with brain metastases because of preclinical predictions about drug distribution into the CNS.

We hope that the introduction of drugs that are effective in Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma metastasised to the brain will result in new trial designs that allow such patients to be included.”

Inevitably, with combination data for BRAF + MEK being presented at this year’s ASCO meeting as highlighted in my preview video, I don’t think it will be long before we see a new trial looking at dabrafenib plus trametinib in this patient population to see whether dual inhibition can overcome the inevitable acquired resistance that develops.

References:

Falchook, G., Long, G., Kurzrock, R., Kim, K., Arkenau, T., Brown, M., Hamid, O., Infante, J., Millward, M., Pavlick, A., O’Day, S., Blackman, S., Curtis, C., Lebowitz, P., Ma, B., Ouellet, D., & Kefford, R. (2012). Dabrafenib in patients with melanoma, untreated brain metastases, and other solid tumours: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial The Lancet, 379 (9829), 1893–1901 DOI: 10.1016/S0140–6736(12)60398–5

Falchook, G., Long, G., Kurzrock, R., Kim, K., Arkenau, T., Brown, M., Hamid, O., Infante, J., Millward, M., Pavlick, A., O’Day, S., Blackman, S., Curtis, C., Lebowitz, P., Ma, B., Ouellet, D., & Kefford, R. (2012). Dabrafenib in patients with melanoma, untreated brain metastases, and other solid tumours: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial The Lancet, 379 (9829), 1893–1901 DOI: 10.1016/S0140–6736(12)60398–5

Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR, Buzaid AC, Cochran AJ, Coit DG, Ding S, Eggermont AM, Flaherty KT, Gimotty PA, Kirkwood JM, McMasters KM, Mihm MC Jr, Morton DL, Ross MI, Sober AJ, & Sondak VK (2009). Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 27 (36), 6199–206 PMID: 19917835

At first view, I was impressed by the enormous organization and very large number of participants, which was at least as important as the ASCO annual meeting. However, as a clinician, I only recognized very few familiar faces as the large majority of attendance included basic and translational scientists, as well as representatives of pharma.

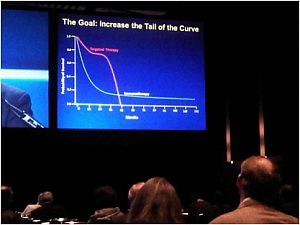

At first view, I was impressed by the enormous organization and very large number of participants, which was at least as important as the ASCO annual meeting. However, as a clinician, I only recognized very few familiar faces as the large majority of attendance included basic and translational scientists, as well as representatives of pharma. The goal is to increase the tail of the curve in the photograph in the right. The approval of ipilimumab in the treatment of metastatic melanoma has inaugurated the new era of anti-cancer immune therapies.

The goal is to increase the tail of the curve in the photograph in the right. The approval of ipilimumab in the treatment of metastatic melanoma has inaugurated the new era of anti-cancer immune therapies.