At the recent annual American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) meeting, Keith Flaherty from Mass General Hospital discussed the latest developments in metastatic melanoma in a plenary session.

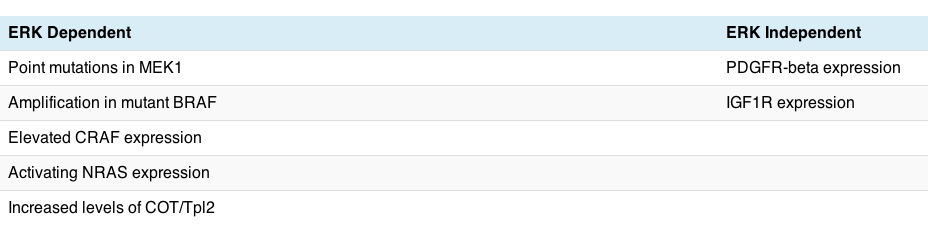

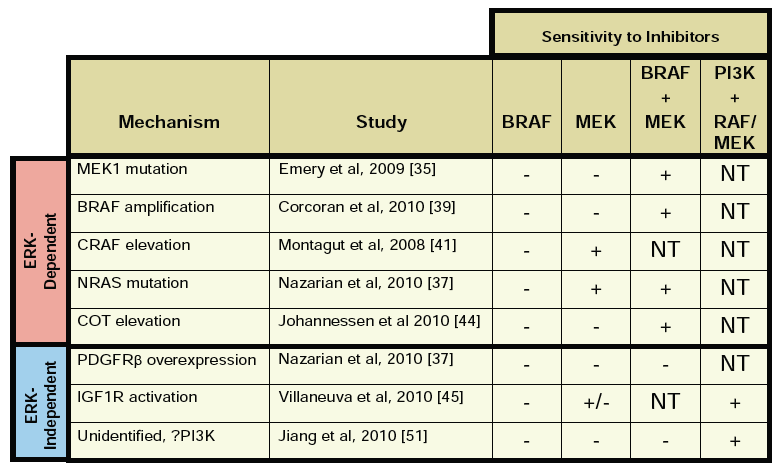

Much of the talk focused on progress to date with existing therapies, new mechanisms of resistance in BRAF V600E driven melanoma relating to COT, based on a recent Nature publication at the end of last year (see references below) and the potential for new compounds in the pipeline.

Remember that BRAF mutations are expressed in only 7% of cancers, but 60% of melanomas and mutant BRAF was seen as a poor prognostic factor until PLX4032 (now known as vemurafenib) came along and achieved some starting results in some patients.

Many of you may recall that we discussed other mechanisms of resistance to PLX4032. You can see in the kinase pathway how COT connects with RAF, so it is not entirely surprising to see an adaptive pathway emerge at this point.

Essentially, what happened is that the scientists looked for possible mechanisms of resistance that may offer new druggable targets to overcome BRAF resistance. The Nature Letter is quite technical, but makes for an interesting read for those familiar with kinase screens and cell lines:

“Here we expressed ~600 kinase and kinase-related open reading frames (ORFs) in parallel to interrogate resistance to a selective RAF kinase inhibitor. We identified MAP3K8 (the gene encoding COT/Tpl2) as a MAPK pathway agonist that drives resistance to RAF inhibition in B-RAF(V600E) cell lines.”

They then went on to explain what they found from this approach:

“COT activates ERK primarily through MEK-dependent mechanisms that do not require RAF signalling. Moreover, COT expression is associated with de novo resistance in B-RAF(V600E) cultured cell lines and acquired resistance in melanoma cells and tissue obtained from relapsing patients following treatment with MEK or RAF inhibitors.”

The good news is that COT is a tyrosine kinase, which means in theory it offers a new druggable target for therapeutic intervention, thus we may see chemists busy working on producing new kinase inhibitors that target COT, thereby offering a new combination down the road for melanoma clinical trials.

In the meantime though, there are some other promising new compounds in the pipeline that I have been watching, making advanced melanoma very much a hot topic of late, especially as much of the progress is based on translational research running in parallel. This may well be the future in cancer research – moving from bench to bedside in a seamless and ever evolving cycle. It also speaks to the value of involving more scientist-physicians in the process to ensure that the learnings are reincorporated into research quickly and efficiently. We need more of this sort of approach elsewhere for rapid progress to be made!

New therapeutic developments

Looking at the clinical trials database, there are many other compounds in development for metastatic melanoma, so all hope is not lost if PLX4032 primary or secondary resistance sets in, since sequencing or combination of different agents may be important in order to delay the onset of drug resistance.

As Dr Flaherty noted in his plenary talk at AACR, the next generation of inhibitors will seek to build on the success of PLX4032, offering further improvements:

- Increased potency and/or selectivity for BRAF

- Pan-RAF inhibitors with increased potency against CRAF

- Dimerization blockers

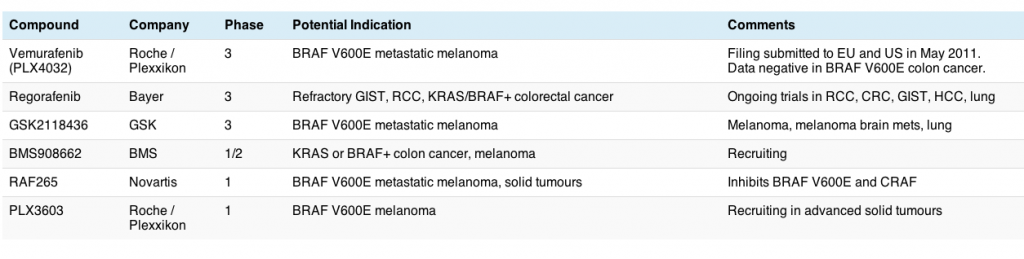

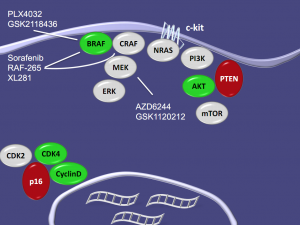

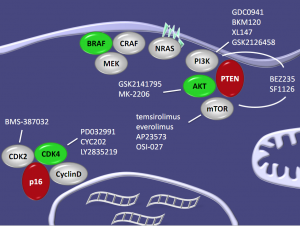

Some examples of the immediate melanoma pipeline for kinase inhibitors include:

- GSK2118432 (GSK) is a selective BRAF inhibitor similar to PLX4032

- PLX4720 (Plexxikon) next generation BRAF inhibitor, targets BRAF and CRAF

- RAF265 (Novartis) targets both BRAF and CRAF

- XL281 (Exelixis) similarly targets BRAF and CRAF

- AZD6244 (AstraZeneca) a MEK inhibitor

- GSK1120212 (GSK) also inhibits MEK

You can see more detail from Dr Flaherty’s talk given at the Targeted Anticancer Therapies Conference in March (PDF link, open access), which is similar to the AACR plenary talk we heard in Orlando:

The advantage of combining BRAF and MEK inhibitors is that you get increased PARP & caspase 3 cleavage at lower concentrations, at least when tested with PLX4720, suggesting that this may be a useful approach if the results are reproduced clinically.

In addition, as we learn more about the biology of the disease, so out knowledge of the importance of related and adaptive pathways also increases. These include many we have discussed on this blog in other tumour types previously, including AKT, PI3K-mTOR, CDK2 and CDK4 as Dr Flaherty showed in this elegant slide:

What next?

My take on all of this is that it’s good to see new combinations emerge to combat various mechanisms of resistance that are evolving, and perhaps potentially reduce the squamous proliferation seen in some patients with PLX4032 due to CRAF being activated.

Overall, it does look like metastatic melanoma will be a hot topic at ASCO if there are some exciting new mature data available for presentation and discussion.

References:

Johannessen, C., Boehm, J., Kim, S., Thomas, S., Wardwell, L., Johnson, L., Emery, C., Stransky, N., Cogdill, A., Barretina, J., Caponigro, G., Hieronymus, H., Murray, R., Salehi-Ashtiani, K., Hill, D., Vidal, M., Zhao, J., Yang, X., Alkan, O., Kim, S., Harris, J., Wilson, C., Myer, V., Finan, P., Root, D., Roberts, T., Golub, T., Flaherty, K., Dummer, R., Weber, B., Sellers, W., Schlegel, R., Wargo, J., Hahn, W., & Garraway, L. (2010). COT drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation Nature, 468 (7326), 968-972 DOI: 10.1038/nature09627

Johannessen, C., Boehm, J., Kim, S., Thomas, S., Wardwell, L., Johnson, L., Emery, C., Stransky, N., Cogdill, A., Barretina, J., Caponigro, G., Hieronymus, H., Murray, R., Salehi-Ashtiani, K., Hill, D., Vidal, M., Zhao, J., Yang, X., Alkan, O., Kim, S., Harris, J., Wilson, C., Myer, V., Finan, P., Root, D., Roberts, T., Golub, T., Flaherty, K., Dummer, R., Weber, B., Sellers, W., Schlegel, R., Wargo, J., Hahn, W., & Garraway, L. (2010). COT drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation Nature, 468 (7326), 968-972 DOI: 10.1038/nature09627